This post will be current as of 1st April, and that means it's time once again for... Diapsida!

The largest species of birds alive today are the ostriches. Since 2014, we have recognised two species of ostrich, but, as the fact it took us that long to notice might imply, they're about the same size, so which is actually "the largest" is debatable, although the common ostrich (Struthio camelus) tends to be the one given the honour.

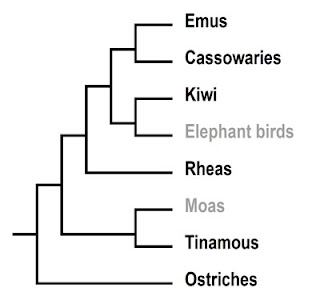

Under the system of classification used throughout the 20th century, ostriches are a kind of ratite, a group of flightless birds, most of which are large, long-legged and long-necked, and all of which lack the keel on their breastbone to which the flight muscles would be anchored in other birds. In 2010, the first evidence surfaced that the ratites were not a natural evolutionary group, when it turned out that the South American tinamous formed a branch within the "ratite" family tree. Since tinamous can fly (albeit not very well) and, more importantly, do have a keel, they aren't ratites themselves, so the old terminology had to be dumped.

Even so, this newly defined group, the "palaeognaths", does sit right at the base of the family tree of living birds. Aside from the tinamous, it consists of five kinds of flightless bird: ostriches, emus, cassowaries, rheas, and the kiwi. With the exception of that last one, these are pretty big birds, freed from the constraints of flight to be able to develop giant size. Although there are other individual species of flightless bird here and there, the only other major group of such animals today are the penguins, which are clearly very different from the likes of ostriches.

In the past, however, there were many other giant flightless birds which had, at least superficially, the same form as the non-kiwi ratites. Some of them, such as the moas of New Zealand, belonged to the same group as the modern ratites, others, such as the terror birds of South America were not. The very largest birds ever to have existed were probably either the elephant birds of Madagascar or the "demon ducks" of Australia, both of which are thought to have weighed over two and a half times as much as the largest living ostrich.

However, all of these true giants do have something in common: they all lived in the Southern Hemisphere. It's not that there weren't large flightless birds in the north, but they weren't quite so large. Some of the terror birds did reach North America in the Pliocene, with Titanis walleri being one of the largest of its kind. Even so, at around 150 kg (330 lbs), it was basically the size of a large ostrich (although it was carnivorous and predatory, which makes it a bit scarier). Gastornis, which lived in both Eurasia and North America, was somewhat larger, but nothing like the size of an elephant bird, and likely smaller than a moa, too.

That's probably the largest bird ever to have lived in North America. Ostriches, the only ratites living north of the equator today, have, at various times in the past made it out of northern Africa to reach Eurasia, and some of them were larger than the modern sort, but not by much. So the picture was a little less clear as to what held the record for the largest bird ever to have lived there - Gastornis or an early ostrich?

I say 'was' because of a new discovery announced last year.

The discovery comes from a cave in Crimea that contains Pleistocene deposits, roughly 1.7 million years old. This is during the earlier part of the Ice Ages, although Crimea would have been well south of the ice sheets, even if the deposits weren't created during an interglacial, which, given the uncertainty in the exact age, is entirely possible. Certainly, the environment seems to have been warm enough at the time, since the same cave has returned fossils of antelope, hyenas, porcupines, and rabbits, along with more obvious 'Ice Age' animals such as mammoths, bison, and sabretooth cats.

The fossil in question consists purely of a thigh bone, which is about 40cm (16 inches) in length, about a third longer than that of a modern ostrich. It's identifiable as having belonged to a bird and, since it's also much thicker than an ostrich thigh bone, clearly not a stork or a flamingo or something of that sort.

In fact, while it's bigger than previously known examples, the researchers who described it were able to assign it to an existing fossil species, Struthio dmanisensis. This was first described in 1990, also on the basis of a thigh bone, recovered from deposits of Georgia of roughly the same age as the Crimean one. It's one of four known species of ostrich from the same general time period and geographic area, which reached at least to Hungary in the west and Turkey in the south. (Having said which, not all of these other species necessarily include thigh bones in their fossils, so some may well have been the same animal named twice).

This raises a couple of interesting questions, of which the most obvious is probably "so how big was the rest of it, then?"

This is, of course, difficult to know. We can't simply take the length of the bone and scale it up, because not all birds have legs of the same proportions. However, the width of the bone may be a better guide, since it gives us some idea of how heavy a body it had evolved to hold up. Using formulae established for this sort of thing, and previously used to estimate the size of demon ducks, the best guess is that this bird weighed around 460 kg (half a ton).

Which, if true, would make this by far the largest bird ever found in the Northern Hemisphere, and second only to the elephant birds and the very largest demon ducks in the south.

The second question, which arises from the fact that we only have some thigh bones, is "was this really an ostrich?"

That's a harder question to answer. The researchers who discovered it point to a number of unusual features in the shape of the bone, other than its sheer size, to suggest that the bird be placed in the genus Pachystruthio, rather than the genus of modern ostriches. Pachystruthio was first used in the 1950s to describe a species of Hungarian ostrich of about the same age as this one, but wasn't considered to be a full genus at the time. That specimen was, however, discovered alongside some fossilised eggshells, which turned out to have some microscopic features that differ from those found in modern ostrich eggs and were also noticeably thicker.

On this basis, the researchers promoted that species, the giant one, and one of the other previously known fossil "ostriches" of the area to genus status as Pachystruthio. But is that merely a technical argument about precise naming, or does it indicate something deeper? That's not a question we can answer without more fossils. If these aren't close relatives of modern ostriches, then, given how little else we know of them, it's possible that they aren't really ostriches at all, but merely something that, like emus, just happened to look similar.

But, despite that, there are a few things we can say about this giant eastern European ostrich. While there may be subtle differences between its leg bones and those of modern ostriches, they are similar enough to suggest that this animal would have been a fast runner as they are. Probably not quite as fast, being so large, but still more so than the largest of elephant birds. Since, unlike elephant birds, this animal also had to cope with living alongside sabretooth cats and giant hyenas, that speed may well have been helpful.

As it happens, though, another predator also makes it first temperate Eurasian appearance in the Georgian deposits in which the earlier fossils of this bird were found. This predator must also have lived alongside the giant ostriches of eastern Europe for at least some time, and, for all we know, may have hunted them too.

That predator, whose exact species is still disputed, was nonetheless a member of the genus Homo. By some definitions, that qualifies them as early humans.

[Photo by Michel Dupont from Wikimedia Commons, cladogram adapted from Cloutier et al. 2019.]

No comments:

Post a Comment