|

| Potamotherium |

Sunday, 17 December 2023

Prehistoric Mammal Discoveries 2023

Sunday, 10 December 2023

Oligocene (Pt 6): Devil's Corkscrews and the Grasseater That Wasn't

|

| Leptomeryx |

Deposits across the continent show a sudden change in the climate at around the dawn of the Oligocene. By 'sudden' in this context, we mean over the course of hundreds of thousands of years, so it's hardly something you would have noticed had you been there at the time, but it's still rapid as such things go. The exact nature of the changes, and the speed at which they appear to have happened, depend on which part of the continent we're talking about, but nowhere was unaffected.

Sunday, 3 December 2023

The Other One: Red Pandas

Saturday, 25 November 2023

The First Whales to Use Sonar?

|

| Xenorophus |

We can put some limits on this. At the younger end, since all odontocetes echolocate, it's unlikely to have evolved any later than their last common ancestor, which is estimated to have lived around 34 million years ago. On the other hand, it's notable that the toothless, baleen, whales do not use ultrasound; in fact, they are specialised in the exact opposite direction to produce sounds well below, not above, the range of human hearing. This suggests that they evolved along different lines, and that the origins of ultrasonic echolocation lie somewhere after the two split.

Sunday, 19 November 2023

Learning to Hunt at Sea

But there comes a point where any mammal has to be weaned and make its way in the wider world. Even then, the maternal investment doesn't necessarily end with the mother continuing to raise and train her offspring for what can be an extended period. Brown bears, for example, are weaned at around six months, but they commonly stay with their mothers for at least another year, and often for two or more. We can see similar patterns in other mammals including, perhaps most obviously, primates.

Sunday, 12 November 2023

Defending the Troops

It's well-known that predators will tend to pick off weaker individuals if they can, largely to save themselves the effort of capturing something that's more able to escape or fight back. But it's also likely that some positions within a herd are going to be inherently safer than others, and merely being fit may not help much if you're an obvious target. The question then arises as to whether certain sorts of individual are likely to occupy safer or more dangerous positions and as to how the group as a whole arranges itself.

Sunday, 5 November 2023

Skunks of the World: Stink Badgers!

|

| Sunda stink badger |

It had been assumed that skunks (as a subfamily of mustelids) lived only in the Americas, much as racoons do. But the genetic studies showed that two species of supposed badger living in Indonesia were not, in fact, badgers at all, but members of the newly erected skunk family. These animals are collectively known as "stink badgers", although the local name of "teludu" and "pantot" are sometimes preferred.

Sunday, 29 October 2023

Oligocene (Pt 5): The First Cats

|

| Proailurus |

Plesictis is an example here. It looked, so far as we can tell, rather like a polecat and was about the same size, so for much of the 20th century it was thought to be an early example of a mustelid, albeit one no more closely related to actual polecats than, say, badgers or otters are. More modern analyses are more circumspect; it may look like a mustelid in some respects, but it probably lived before those animals diverged from the raccoons and so can't be quite either. Palaeogale, which looked rather similar and was also originally assumed to be a mustelid, in fact turns out to be more related to cats and mongooses, but probably so far down the family tree that it's not yet possible to say much more than that.

Sunday, 22 October 2023

Follow the Leader?

By human standards, the majority of mammal species are comparatively antisocial. Some actively avoid others of their kind outside of the mating season, but even those that are more tolerant are often found together in one place purely because that is where the food happens to be. But, of course, there are a great many exceptions to this; animals that habitually live in groups that socialise and travel together.

By human standards, the majority of mammal species are comparatively antisocial. Some actively avoid others of their kind outside of the mating season, but even those that are more tolerant are often found together in one place purely because that is where the food happens to be. But, of course, there are a great many exceptions to this; animals that habitually live in groups that socialise and travel together.

Animals that live like this have to have some form of decision-making process that all members of the herd, pack, or other grouping choose to abide by. The most obvious example of this would be deciding when and where to move, but it could also include, for example, determining the best way to escape predators. Lacking the sophisticated communication methods of humans, concepts of debate aren't likely to be applicable, but the decision has to be taken somehow, and, over the years, there have been many studies to determine just how egalitarian the process is and exactly which animals within the group are making the decisions if it isn't.

Sunday, 15 October 2023

Attack of the Giant Hyenas

|

| Dinocrocuta |

This isn't some new discovery on the basis of molecular evidence, like the splitting off of the skunks from the weasel family; it's been known for a long time. This is because, when you start looking at the structural details of the skull, especially the area around the ear, everything fits with a cat-like ancestry. This much was already obvious when Miklós Kretzoi formally named the two carnivoran branches while he was working at the National Museum of Hungary during World War II. Modern evidence has merely confirmed the view, showing more precisely that the closest living relatives of the hyenas are the mongooses.

Sunday, 8 October 2023

Skunks of the World: Hog-nosed Skunks

|

| American hog-nosed skunk |

Saturday, 30 September 2023

Hammer-Toothed Snail Eaters

Although they represent almost a third of non-American marsupial species, dasyuromorphs are far less diverse than their herbivorous counterparts, with all but one of the living species belonging to a single family, the dasyurids. Although the most famous example of the dasyurids is probably the Tasmanian devil, which eats comparatively large prey, most of the other species are small shrew-like animals feeding on insects. Alongside them, we can place the numbat and the extinct thylacine ("Tasmanian tiger" or "wolf") both of which are odd enough to be placed in families of their own.

Sunday, 24 September 2023

Return of the Rabbits?

.jpg) |

| This one is wearing a radio collar... |

Sunday, 17 September 2023

We're Up All Day to Get Lucky

In reality, however, it turns out that this can have a lot to do with the circumstances. And, in the modern world, those circumstances are most likely to be shaped by... what else, but humans?

The issue, of course, is that humans are for the most part diurnal. Which isn't much of a problem for animals that are naturally nocturnal, but can be if they, too, would prefer to be active during the daylight hours. What we see time and time again across the world, and across different mammal species, is that where humans are most likely to encounter wild animals, those animals shift their behaviour towards nocturnality to avoid the stress of meeting us too often.

Sunday, 10 September 2023

Skunks of the World: Spotted Skunks

.jpg) |

| Eastern spotted skunk |

That honour goes to the spotted skunk, which appeared in the earliest recognised list of scientific animal names in 1758. This isn't to say that nobody knew at the time what a striped skunk was, merely that the naturalists of the day had yet to identify them as something distinct from the spotted sort, and it was the latter that happened to be described first - the striped skunk followed less than twenty years later, in 1776. Before they were given their own genus, both species were originally placed in Viverra, which comes from the Latin word for "ferret" but seems to have been used for any small, slender mammalian carnivore that didn't fit elsewhere (not including, ironically, the ferrets).

Sunday, 3 September 2023

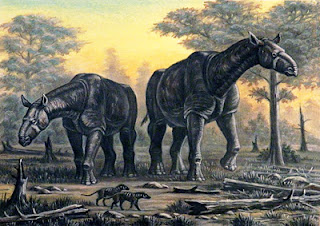

Oligocene (Pt 4): Time of the Giants

|

| Paraceratherium |

At first glance, since the oldest fossil is German, it appears that tapirs originated in Europe and then spread east, and it's purely a coincidence that they happened to do so after the Coupure - which, after all, was a time of climatic change. The problem is, there wasn't anything remotely tapir-like living in Europe before the Coupure, but there were plenty of potential ancestors elsewhere. So it's perhaps more likely that the first true tapirs were Asian, and we simply haven't found their fossils yet. Even so, we can at least say that Protapirus, and its later relative Paratapirus (which never seems to have left Europe) really were tapirs, rather than some close relative. A key feature here is that, unlike their earlier relatives, they already had the modifications to the nasal bones that suggest the presence of the short trunk that modern tapirs have, although it was probably less prominent than in current species.

Sunday, 27 August 2023

Picking the Right Crevice

The problem with caves as a habitat, however, is that, in the grand scheme of things, they aren't all that common. Clearly, this depends on the type of landscape you're in, but many places just don't have lots of caves. In the tropics, hanging from a tree branch might well be sufficient, but where the weather is cold, especially in winter, that may not be such a good idea. So bats roost in many other places, too, such as hollows in trees and cracks and crevices in the ground that are similar to, but much smaller than, what we'd normally think of as a "cave".

Sunday, 20 August 2023

Love on the Mountain Tops

There are, as with many animal groups, more species of caprine than one might at first think, and I covered them all individually about ten years ago. Looking through that series, it should be possible to appreciate that the group is also varied, not only inhabiting a range of environments but also living varied lifestyles, from those that are near-solitary to those that prefer large herds. This is also reflected in their mating habits which, are as one might expect, related to the size of the community in which they live. One would also expect that the habitat would have some effect on how the animals choose to live, and, in turn, on that mating behaviour.

Sunday, 13 August 2023

Skunks of the World: Striped and Hooded Skunks

.jpg) |

| Striped skunk |

It's hardly surprising; the striped skunk is the most widespread and common of all the species of skunk and surely the most familiar to most North Americans and hence, indirectly, to most Europeans. (For what it's worth, while all the naturalists named above were French, Bonaparte had at least spent a few years working in the US, and was probably much more familiar with skunks than his predecessors). Indeed, the striped skunk lives across the whole of the contiguous US, save only the Mojave Desert and the Great Basin of southern Nevada. It's also found across most of southern and central Canada, and, being no respecter of the US Immigration Service, also into northern Mexico.

Sunday, 6 August 2023

Not-Quite Placentals of the Gobi Desert

The great majority of living mammals species are placental mammals, the marsupials representing what is, today, a comparatively small side-group. They are distinguished by the young gestating in the womb for a comparatively long period of time, taking in nutrients through a fully-formed placenta. There are other features that unite them, too, such as the basic number of teeth, although these are often obscured by the considerable evolution and change of form that has occurred in some placental groups to create animals as diverse as horses and dolphins.

Sunday, 23 July 2023

A Puma's Larder

But that's not necessarily the end of the story. Many animals cache a proportion of their food, saving it for later. One immediately thinks, perhaps, of squirrels storing their nuts so that they can come back to them in winter when food is in short supply. Many burrowing rodents do something similar, hoarding food in underground chambers that can return to at their leisure. But carnivores can cache food, too, despite the fact that meat tends to go off more quickly than properly stored nuts or grain.

Sunday, 16 July 2023

The Stinky Family: Skunks

Sunday, 9 July 2023

Oligocene (Pt 3): From Musk Deer to Hell-Pigs

|

| Entelodon |

These include the gelocids, which first appeared close to the end of the previous epoch. Few of the known fossils of these animals are in good condition, and there is some debate as to whether they are a true group of animals at all, or just a vague term used to collect similar-looking creatures that we can't place elsewhere. That aside, we can at least say that they physically resembled (but were probably not related to) musk deer. That is, they were relatively small, hornless animals with long legs suited for running fast, but lacking the large fang/tusks that mark true musk deer. They did well enough that some, such as Pseudogelocus, are known not only from France and Germany, but also Mongolia, suggesting that they crossed over in the opposite direction to most other mammal groups.

Sunday, 2 July 2023

The Sex Lives of Female Jaguars

Monogamy is somewhat less common. Sometimes, it happens only because the species is sufficiently widespread that any given male is unlikely to find more than one receptive female during the breeding season, but it can also occur by choice, typically where raising young is a sufficiently arduous task that the father has to stay around after the birth to help. This is commonly associated with birds, but many mammals also form pair bonds for raising young. These include species of gibbon and small antelope that, in paternity tests, have shown essentially 100% loyalty to their mates. The prairie vole is well-studied in this regard, with the formation of the pair bond through prolonged and repeated mating having been linked to, among other things, the "cuddle hormone" oxytocin.

Sunday, 25 June 2023

Pennsylvania Elk with a Wyoming Accent

Since animals don't have language in the human sense, we might not expect the same thing to be true of them. Animals have distinct vocal repertoires, but these are largely instinctive, and a cat goes 'miaow' regardless of where it lives. (Well, arguably it goes 'meow' if it's American and 'nyan' if it's Japanese, but you get the point). It's perhaps not surprising that there is variation between individual songbirds of the same species, or among cetaceans, given the complexity of their calls, but we might not think of it among terrestrial mammals.

Sunday, 18 June 2023

The Raccoon Family: Olingos

|

| Northern olingo |

This was William Gabb, who had been asked by the government of Costa Rica to conduct a three-year biological survey of the Talamanca region, on their eastern border with Panama. He completed the survey in 1876, but died two years later from malaria contracted while on the expedition. His real expertise was in dinosaur fossils so when he discovered a previously unknown species of living mammal, he sent the skull and pelt to Joel Asaph Allen at Harvard. Granted, he was an ornithologist (he would later help to set up the Audubon Society) but he did also have an interest in mammals, and was able to identify the animal as a new member of the raccoon family "as unlike [raccoons and coatis] as these... are unlike each other".

Sunday, 11 June 2023

A Tale of Three Ground Sloths

Ground sloths, however, are not a single type of animal in the strict biological sense. This is because the two-toed and three-toed sloths that we have today are not especially close relatives, last sharing a common ancestor at least 28 million years ago. In fact, tree sloths evolved twice, in separate branches of the sloth family tree, and some ground sloths were more closely related to one or the other. On this basis, we used to divide the ground sloths into two families, but the fact that some of lived recently enough that we can recover and analyse DNA from their fossils gave us some surprising detail and a key 2019 study suggested that we should consider there to be no fewer than six different families of ground sloth.

So whatever we can say about one sort of ground sloth isn't necessarily true of all the others, even on quite a broad scale.

Sunday, 4 June 2023

Social Posting - Bear Style

At least among mammals, there are two primary modes of communication that are generally studied by researchers. Perhaps the more obvious of these to we humans is vocal communication, since that's the main one we used in pre-literate societies. Not all species are especially vocal, but many are, and some are using sound outside of the human hearing range - such as the ultrasound squeaks of many small rodents such as mice. One estimate suggests that around 95% of mammal species use acoustic communication and this may be on the low side (it's 100% in birds and 90% in amphibians, but apparently less than 5% in reptiles, suggesting that it has evolved at least three times).

Saturday, 27 May 2023

When the Desert is Too Dry

|

| The round-tailed ground squirrel lives further east, and is not threatened |

The size and relative location of such territories naturally vary between species, but also depend on the local conditions of terrain, climate and so on. The harder it is to find food, for instance, the larger your territory will need to be. As young animals grow up and leave home, they will need to find unoccupied territories to inhabit, or else somehow drive an existing resident out and take over. Males commonly travel further than females so that they don't end up with only their sisters or close cousins as potential mating partners, although there are a few species where it works the opposite way around.

Sunday, 21 May 2023

The Raccoon Family: Kinkajous - the primate-like "raccoons"

Perhaps the most distinctive, and certainly the most studied, of these is a genus with just one species: the kinkajou (Potos flavus). It was first scientifically described by Johann Schreber in 1774, in an earlier volume of the book in which he would later describe (among other things) cheetahs, snow leopards, and bobcats. While he was understandably clear those were all cats, the identity of the kinkajou was not so obvious. In the days before Darwin, this may not have held any deep meaning for him, but his conclusion was that his new animal was a kind of lemur.

Sunday, 14 May 2023

Oligocene (Pt 2): Europe's Big Break

|

| Eomys |

Prior to the Oligocene, it would have been possible for a hypothetical traveller to sail from what is now the eastern Mediterranean, through the Paratethys Sea (now the Black and Caspian Seas) due north and into the Arctic Ocean. The body of water that made this possible, the Turgai Strait, was already becoming shallower and narrower as the Oligocene approached, and the sudden dip in sea level finished it off altogether, closing off the sea route that had once run along the eastern flank of the Ural Mountains.

Sunday, 7 May 2023

Cheetahs and Wild Sheep

This does, however, disguise some significant regional variation.

How we should divide the cheetah into subspecies is not absolutely clear. From at least the 1970s, five subspecies were recognised, Two of those were merged in 2017, on the grounds that the East African form could not be reliably separated from its southern relative genetically. Even then, cheetahs have so little genetic variation across their range - due to an apparent population bottleneck when they almost died out at the end of the Last Ice Age - that support for the existence of two of the other subspecies remains a little shaky. Still, four subspecies is, for the time being, the general consensus.

Sunday, 30 April 2023

The Pandas of Bulgaria

This, of course, is the subfamily of the pandas, the Ailuropodinae. Pandas are sufficiently odd that it was unclear for a time whether they were really bears, or something else, although their status hasn't really been in doubt since the 1980s when genetic evidence proved what had, even then, been suspected for a couple of decades. Today, only one species of ailuropodine exists, the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), and it is found only in China. The same evidence used to estimate the split between the other living subfamilies puts the date of the split between pandas and other bears much further back, to around 20 million years ago, not long after the dawn of the Miocene.

Sunday, 23 April 2023

The Raccoon Family: Cacomistles

|

| Ringtail |

The scientific name didn't stand, because it turned out that the first part of it had already been used for a kind of butterfly. Furthermore, while he originally referred to the animal by its Spanish name "cacomixtle", since the specimen he knew of came from somewhere near Mexico City, in English we now call it a ringtail (Bassariscus astutus) or, less accurately, a "ring-tailed cat". Even so, in many parts of the US, an Anglicised form of the Spanish name is still in wide use.

Sunday, 16 April 2023

The Life and Habits of the Father of Cats

Even if we look at the fossil record, we find that for millions of years, the great majority of such animals were also members of the Carnivora even if, in some cases, their specific family no longer exists. The great majority, but not all. In 1875, American palaeontologist Edward Drinker Cope coined the term "creodont" for a collection of early carnivorous mammals that lacked the key defining features of the carnivorans. His original definition was relatively narrow, but over the next few decades it was expanded until, in 1909, it came to include essentially all of the large land-dwelling carnivorous placentals that weren't carnivorans.

Sunday, 9 April 2023

Decline of the Sea Otters

Sea otters (Enhydra lutris) are an endangered species, native to the coasts of the northern Pacific from Japan to California. I've discussed them in detail before, but suffice it to say here that they are remarkable creatures, able to survive without setting foot on land, digging no dens as other otters do, and even giving birth at sea. They also have the densest fur of any mammal, making it especially valuable.

Which, of course, explains how they became an endangered species in the first place.

Humans have been hunting sea otters for their fur for many centuries, but for much of history, this was small scale, with the local tribes being unable to make any lasting dent in their numbers even if they had wished to. Estimates for the worldwide population of sea otters prior to the 18th century are naturally difficult to come by, but it may have been as high as 300,000. The herald of coming doom came in 1741.

Saturday, 1 April 2023

First of the Falcons?

|

| Crested caracara |

Trying to figure out the higher-level evolutionary relationships among animals can be tricky. Until the last few decades, we had to rely on physical comparisons and visible points of similarity, essentially a more sophisticated and well-informed version of what Linnaeus did back in the 18th century. With lower-level groups this can be reliable; nobody is surprised to discover that a moose is a type of deer or that rats are related to mice. But even here, parallel evolution can leave a misleading signal. It is not, for example, obvious that hyenas are more closely related to cats than to dogs (although, of course, they're neither).

This problem gets bigger when we move to higher-level groups where physical similarity is no longer a reliable guide at all. Is a mouse more closely related to a dolphin than an elephant? That's not an easy one to answer on physical grounds alone. (Dolphin, probably, before anyone asks). It's much the same with birds.

Sunday, 26 March 2023

The Raccoon Family: Coatis

|

| White-nosed coati |

These two animals were coatis (or "coatimundis"), with one first identified from Mexico, and the other from Brazil. They were given their own genus by Gottlieb Storr in 1780 when he first named the raccoon family. It's probably fair to say that, to modern eyes, Storr's classification seems the more reasonable of the two; coatis look a lot more like raccoons than they do like civets.

Sunday, 19 March 2023

Age of Mammals: The Oligocene (Pt 1)

When Charles Lyell devised the current system of dividing the "Age of Mammals" into epochs in 1833, he originally defined four. A few years later, he revised this to five, but even then, the entirety of what we'd now call the Paleogene was placed into a single epoch, the Eocene. In 1854, however, German palaeontologist Heinrich Beyrich, split off the later part of the Eocene into a new epoch, which he saw as a distinct period of transition in the development of fossil seashells. He called this the Oligocene, and it proved useful beyond his original mollusc-based definition, and so has remained in use to this day. (Beyrich's wife, incidentally, was a children's author, and made the unusual step of favourably commenting on the work of Charles Darwin in a novel for young girls at a time when it was still controversial).

Sunday, 12 March 2023

Fruit Bats of Madagascar

On the other hand, it is true that the majority of bat species are not especially threatened, at least on a worldwide scale - although things may be different locally. Bearing in mind that around one in six bat species are so recently identified and so little studied that we simply don't know how common they are, only around another one in six are rare enough to be listed as "threatened" by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Still, that's not exactly a small proportion, and since there are somewhere around 1,400 named species of bat, it's not small in absolute terms, either.

Tha bats are a highly diverse group, representing no fewer than 21 taxonomic families, none of which are likely as familiar to the layman as terms such as "cat family" or "deer family". Some of these contain very few species, representing oddities that don't quite fit into any of the main subgroups, but there are still five families with over a hundred species each. Of these, the one that contains the highest proportion of threatened species is the fruit bat or "flying fox" family, the Pteropodidae.

Sunday, 5 March 2023

Friendship and Fission-Fusion

Here, rather than having a long-lasting association, perhaps bonded by ties of family, the animals live in groups but the membership of that group is not constant. New animals are constantly wandering in, while others break off and leave for other groups. On a larger scale, it may be that the individual fission-fusion groups - the actual bands of animals you would see travelling together - are themselves gathered into larger social networks that may have a relatively consistent structure. That is, the new animals joining the group aren't random; they're individuals already known to the group, and rival social networks may exist nearby that do not mix their members.

Sunday, 26 February 2023

The Raccoon Family: The True Raccoons

|

| Common raccoon |

The common raccoon is found across almost the whole of the contiguous United States, barring only some of the drier parts of the Great Basin, as well as across southern Canada and virtually all of Mexico and Central America. Furthermore, raccoons were introduced to Germany as a hunting animal in 1927 and, with the help of others that escaped from fur farms, since around the 1970s they have been expanding rapidly across Europe. Over the last couple of decades, they have established populations from Spain and France in the west across to Russia and Ukraine in the east. In the 1990s, they were also introduced to Japan and they have also been introduced to Uzbekistan and other parts of Central Asia, probably following escapes from fur farms.

Sunday, 19 February 2023

Tree-Dwelling Almost-Lemurs of the Canadian Arctic

The most northerly island in Canada is Ellesmere Island, whose most northerly point is not far from being the most northerly piece of solid land on the planet, only beaten by parts of Greenland. Midsummer temperatures reach a daily high of about 9°C (49°F) in midsummer, and it often snows in July. Winter temperatures regularly drop below -35°C (-31°F) on January nights. So, yeah, that's uncomfortable.

Sunday, 12 February 2023

Benefits of a Deadly Predator

The reality is more complex than this. Secondary predators also eat herbivores, omnivores are common, really large herbivores aren't likely to be eaten by anything, there may be more than two steps in the chain of carnivores, and we can't forget the detritivores and fungi. And so on. So what we actually have is a "trophic web", a complicated set of interactions where some animals don't fit neatly into a single level on the pyramid. Nonetheless, that doesn't make the basic idea useless and one of the concepts it leads to is the apex predator - the large carnivores that have no predators of their own (at least as adults).

Sunday, 5 February 2023

Haring About

On the other hand, many species are widespread with large populations and seem to be happy in a variety of different habitats. Often, these are animals with a broad diet, able to eat a range of different foods and still remain healthy - the red fox is a good example of this, especially once it started exploiting suburban habitats in the 20th century. Typically, they will not be as good at finding or processing these foods as those that specialise in one particular type but the fact that they can switch food sources easily makes up for this. Indeed, this can be a driver for evolution - an animal becomes really good at exploiting one narrow food source, out-competing the generalists, but the latter remain in the background and, when the world changes and the narrow food source is replaced by something different, become the basic stock from which the next round of specialists will arise.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_Zoo_Salzburg_2014_h.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(captive_specimen)_(9671552427).jpg)

_(16365830393).jpg)

.jpg)