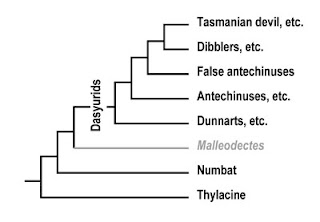

Although they represent almost a third of non-American marsupial species, dasyuromorphs are far less diverse than their herbivorous counterparts, with all but one of the living species belonging to a single family, the dasyurids. Although the most famous example of the dasyurids is probably the Tasmanian devil, which eats comparatively large prey, most of the other species are small shrew-like animals feeding on insects. Alongside them, we can place the numbat and the extinct thylacine ("Tasmanian tiger" or "wolf") both of which are odd enough to be placed in families of their own.

Fossil dasyuromorphs are not common, but they do exist, with most of them discovered at the same Riversleigh deposits that many other fossil marsupials have been. Most of these fossils are sufficiently well-preserved that we can place them into one of the two living subfamilies of dasyurid and we know of at least seven species of fossil thylacine. There are, however, a few fossil species from the site that we just can't place into any of the living families, whether because of incomplete remains, or because they're too primitive to make an easy decision either way.

Or because they're really weird.

Such is the case for Malleodectes, first described in 2011 from a partial upper jaw that was around 12 to 15 million years old. That original paper classifies it as "Metatheria incertae sedis" which loosely translates as "we think it's a marsupial, but beyond that, we're stumped". In fact, the researchers say that, if the roots of the teeth had not been obviously mammalian in form, they might have thought it was a skink.

So what was so odd about it? It had three premolars, which is what you'd expect of most marsupials, so nothing odd there, but the last of those premolar teeth was anything but normal. For one thing, it was huge, with twice the diameter of any other teeth in the jaw. This is what made it look like a lizard, because certain skink species do have an exceptionally large tooth in roughly that position of the jaw. Moreover, the tooth in question had no blade, having a domed shape like a ball-peen hammer so that it couldn't plausibly have cut anything. It also had four roots, something never seen before in any marsupial, implying that whatever it was used for required considerable bracing.

Thus, the scientific name Malleodectes mirabilis, which translates as "extraordinary hammer-biter". A second species, M. moenia, was named at the same time, but remains known from only a single tooth. In 2016, a more complete upper jaw of the first species was described, giving a clearer view of the molar teeth behind the strange one and it was this that led to the researchers deciding that it was probably a dasyuromorph. That it was still very odd meant that it clearly didn't belong in any of the three known families and it was accordingly given its own one - the only recognised dasyuromorph family other than the three that survived into historical times.

And that has been the status for the last seven years - two pieces of upper jaw and one isolated tooth, belonging to two species between them, in a rather uncertain evolutionary position relative to more conventional marsupials. To learn more about these odd creatures, we'd need more specimens, preferably from some other part of the body. Which is now what we have.

A significant issue is that the new specimens - and there are two of them - consist only of sections of lower jaw. That means there's no overlap between them and the older specimens; nothing that we can see in both that means we can definitely say "yes, these belonged to the same sort of animal".

Indeed, these two pieces of jaw can't possibly belong to either of the known species, because they're far too small. Clearly, it's difficult to get a good estimate of the body size of an animal when all you have is a few bits of jaw, but there are at least some methods of guessing based on the proportions of other animals. Using a formula devised specifically for marsupials, the researchers estimated that the animal their new fossils belonged to weighed around 90g (3 oz.) - about twice as much as a house mouse. There's a lot of uncertainty in this, but using the same formula on M. mirabilis indicates that that would have weighed around 900g (2 lb.), similar to a hedgehog.

It's pretty clear that those are not going to be the same species. But what the new specimens do both have is a greatly enlarged, dome-shaped, second premolar similar to the giant tooth on the upper jaws of the previously known species. The third lower premolar has the same unusual shape as well, although it is more normal in size. That seems good evidence that the new animal is a close relative, although whether it's a new example of Malleodectes itself, or some new genus in the same family, isn't something we can say with certainty until we can get a pair of jaws that actually match.

But, if we can't compare the lower jaw of this smaller malleodectid with those of the previously known species, we can compare it with those of other carnivorous marsupials. Performing that analysis on the same basis as a 2017 study looking at the whole group gives strong backing evidence that the creature is, indeed, a dasyuromorph that belongs to none of the modern families. Specifically, it turns out to be a very close relative of the dasyurids, far more closely related to them than to the numbats or thylacines, but still not quite within the group.This leaves the question of what exactly Malleodectes was eating that required it to have uniquely shaped teeth. The hammer-like teeth suggest that the animal was trying to crack something, rather than tearing flesh, and the lower jaw appears too slender for it to have resisted the stresses that would be caused by struggling prey. It could have been a scavenger, cracking bone like a miniature hyena, but, if it were, we'd expect the other teeth to be modified for chewing up the fragments - as they are in both hyenas and Tasmanian devils.

By rescaling the jaws from the two different species so that they're the same length, and lining them up against each other, it now appears that the huge upper tooth would have crushed food against the two teeth behind the enlarged ones in the lower jaw, and those would have engaged with the canines and first premolars in the upper. That makes the crushing surface longer than we had previously thought, a bit like a nutcracker. Every other indication is that it was a carnivore, however, so nuts may also have been off the menu.

This basically leaves us with the theory originally proposed when the first fossil was discovered, and that compares it to the diet of the pink-tongued skink, a lizard with similar-looking teeth. That mainly eats slugs and snails, and it uses the hammer-shaped teeth to crush snail shells, with the rest of the prey animal being soft enough that it doesn't need the modifications we'd see in a bone-crusher. While this new fossil belonged to a species much smaller than the previously known ones, that hardly disqualifies it from eating snails.

While there are some mammals, such as certain kinds of otter, that specialise in eating shellfish, one that feeds primarily on snails would be an oddity. But, while we can't be certain, it remains the best bet for what this peculiar little marsupial was up to.

[Photo by Pascal Abel, from Wikimedia Commons. Cladogram adapted from Churchill et al. 2023.]

No comments:

Post a Comment