This, of course, is the subfamily of the pandas, the Ailuropodinae. Pandas are sufficiently odd that it was unclear for a time whether they were really bears, or something else, although their status hasn't really been in doubt since the 1980s when genetic evidence proved what had, even then, been suspected for a couple of decades. Today, only one species of ailuropodine exists, the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), and it is found only in China. The same evidence used to estimate the split between the other living subfamilies puts the date of the split between pandas and other bears much further back, to around 20 million years ago, not long after the dawn of the Miocene.

We don't have any clear panda fossils going quite that far back, but there are still several that at least date back to the Middle or Late Miocene. Or at least, animals that we could potentially call "pandas". The confusion arises because, when it comes to fossil species, not only the placement of the panda subfamily but its exact membership has changed several times since it was first named in the late 19th century.

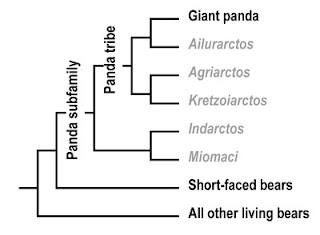

There seems to be good evidence, for example, that the Late Miocene Indarctos, an omnivorous animal about the size of a brown bear, was more closely related to giant pandas than to other living bear species. As a result, it's usually placed in the panda subfamily today, even though, arguably it wasn't that much like living pandas and it probably split off from their ancestors not long after the subfamily originated. In 1980, therefore, the panda subfamily was split into two tribes, one containing Indarctos, and one containing what we might call, for lack of a better name, the "true" pandas.

So, passing over this other tribe of not-quite pandas, what are we left with? Again, there has been some dispute about what should and should not be included, but the current state of play seems to be broadly as it was laid out in a study published in 2012. That recognised four genera within the "true" panda tribe. One of these is obviously the living one, Ailuropoda, which includes the giant panda itself and at least two species that lived in eastern Asia during the Ice Ages; they're probably "chronospecies", which is to say, direct ancestors of the modern form whose fossils happen to represent particular points along a single evolutionary path.

How the other three genera, the Late Miocene Ailurarctos and Agriarctos and the Middle Miocene Kretzoiarctos, relate to the living form is more debatable. Notably, they were not all native to eastern Asia. Ailurarctos is the exception. First described in 1989 and given a name that literally translates as "cat-bear" but is probably intended to imply "panda-bear", this lived in southern China and has recently been shown to have already had the "false thumb" that living pandas use to hold onto bamboo.

It seems to be generally accepted today that Ailurarctos is the ancestor of the modern panda genus or at least as close a relative as we're ever likely to find. Where the other two stand is much less obvious, not least because their remains are fragmentary and often missing some of the more diagnostic bits.

While Kretzoiarctos is still known only from Spain, numerous species of Agriarctos have been named over the decades, with remains from France, Germany, and Greece in addition to the originals from Hungary. These are often little more than a few teeth and it's unclear how many are genuinely species, whether they should really all belong in the same genus if they are or, in some cases, even if they're pandas. Even so, last year a new species was named from 5 million-year-old deposits in a part of Bulgaria that would, at the time, have been swampy forest.

The authors of the description concede that, since all they have are a couple of teeth and given the ongoing confusion about the membership of the genus, they are not totally sure that their new species genuinely belongs in Agriarctos. But the teeth happen to be the right ones to prove it's a panda, and there are no other currently named genera of panda living at that time and place, so that will have to do until and unless something better comes along.

The tooth that demonstrates the clearest link with pandas is a carnassial, which in most carnivorous mammals is used to slice flesh but here seems to have adaptations, mirrored in other putative Agriarctos species, that show the animal was already moving towards herbivory. The other is a canine tooth, and surprisingly large. Taken on its own, we'd probably think it belonged to a predator, but perhaps, in this case, it was used in defence or in fighting other bears for access to mates.

The authors also add that the carnassial tooth does not seem adapted to eating tough woody plants like bamboo and argue that the same was true of the teeth of the Chinese Ailurarctos. On the other hand, we know that that had a "false thumb" suitable for holding bamboo, which we don't know of Agriarctos since we don't have samples of its paws. The authors argue that perhaps it initially evolved to hold onto twigs while the panda munched on softer leaves and only later acquired its modern purpose, but this is perhaps rather speculative.

The question of how the "true" panda genera relate to one another remains open. The Spanish Kretzoiarctos is the oldest known example, being the only one to significantly predate the Late Miocene. Thus, one possibility is that pandas were not originally Chinese, but European. One descendant of this early ancestor crossed Asia to give rise to Ailurarctos and its descendant, the modern panda, while the other remained at home, evolving into Agriarctos and dying out during the Messinian Salinity Crisis at the end of the Miocene.

However, since there really aren't any fossil deposits of the right age in the relevant parts of Asia, and the really diagnostic parts of Kretzoiarctos (specifically the upper jaw) are missing, this is not the only option. The alternative is that pandas originally evolved in Asia, perhaps in northern India, and later split into two lineages, one heading west to Europe and the other east towards China.

Without further fossils, whether from Spain or China, deciding between these two possibilities remains an open question.

[Photo by Werner Hölzl, from Wikimedia Commons. Cladogram adapted from Abella et al. 2012, Krause et al. 2008, and Jiangzuo & Spassov 2021.]

No comments:

Post a Comment