|

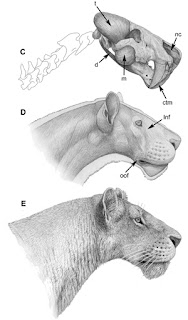

| New reconstruction of the sabretooth cat Homotherium, showing that the teeth would not have been as visible as popularly supposed |

Large Herbivores

Probably the most distinctive thing about deer is that the males have antlers; branching bony head ornaments that are shed and regrown each year. This naturally raises the question of how this evolved, since no other animal has quite the same thing. Acteocemas was an Early Miocene deer, but despite living very early in the group's evolutionary history, it already had antlers that split into two near the tip - which the horns of animals such as cows and true antelopes never do. A Spanish fossil of the antlers described earlier this year showed that it was already shed and regrown, but microscopic analysis indicated that it appeared to have been present for over a year, suggesting longer a more irregular pattern of shedding that must have changed to the seasonal pattern we are familiar with more recently, perhaps in the Middle Miocene.

Among more traditionally horned animals, fossilised hoofprints from the neighbourhood of Cadiz dating back around 100,000 years turned out to be the oldest-known footprints of aurochs, the ancestors of modern cattle. Further east, in Crimea, a fossil unearthed shortly before the recent Ukrainian unpleasantness revealed the presence of Soergalia, an Ice Age musk ox previously only known from Western Europe.

When it comes to microscopic analysis of the fossils of large herbivores, they don’t come much bigger than elephants… or, at least, their prehistoric relatives. Analysis of the isotopes in the tusk of a male American mastodon (Mammut americanum) was able to reveal how the landscape it lived in (and the food it was therefore eating) changed through its life. The results indicated that the animal must have begun migrating more as it aged, adopting a summer-only range, inferred to be its mating ground.Carnivores

The most

famous of prehistoric mammalian carnivores are surely the sabretooth cats, which we generally think of as large and fearsome predators. A new fossil described this year shows that there may have been more variety, even late on in their evolution than we might suppose. Taowu lived in northern China about two million years ago. Representing a previously unknown side-branch in the “dagger-toothed” cats, themselves a side-branch to the line containing Smilodon, it was smaller than its contemporaries, more the size of a leopard than a lion or a tiger.

>Elsewhere in the world of prehistoric cats, the European jaguar (Panthera gombaszoegensis) has long been something of a puzzle, since it hasn’t been clear how it’s descendants or close relatives could have ended up so far away in the Americas. A new analysis of a relatively complete skull suggests that, while its teeth do indeed look remarkably jaguar-like, the rest of its skull is less so than previously thought. The authors suggest that it may actually be a closer relative of tigers, which might explain

quite a lot.

In a similar vein, a detailed scan of the inside of the skull of an “American cheetah” (Miracinonyx trumani), a very fast-running cat already known to be a relative of the puma/cougar/mountain lion, showed that its brain resembled that of real cheetahs and that the degree of convergent evolution between the two was not as great as previously thought.

The name Patriofelis (literally “father of cats”) might suggest that the animal in question was another kind of cat. But it wasn’t even in the same order of mammals, but instead an oxyaenid, one of the carnivores that dominated the Earth back in the Eocene, long before cats or dogs existed. It had unusually short legs, looking a little like a leopard-sized otter, leading to suggestions that it might have been semi-aquatic. A new analysis of its limbs and backbone refutes that idea, as well as the theory that it might have regularly climbed trees. Instead, it was likely a powerful ambush predator with flexible forelimbs for grappling prey.

Just about the least carnivorous carnivoran alive today is the giant panda, the only surviving member of an early side-branch in the larger bear family. This year, not only was a new species of European panda identified in Bulgaria, but, more significantly, the wrist of a panda of similar age from Yunnan Province, China received a detailed write-up. It turns out that it already possessed the fully-formed “second thumb” for which living

pandas are so well-known – actually an enlarged and flexible wrist bone. This suggests that, even 7 million years ago, the pandas of China were eating a large quantity of bamboo and needed the “thumb” to hold it.

Other Placentals

The Middle Miocene rodent Miopetaurista was already known, from analysis of its limb bones to have been capable of gliding between trees and thought to be an early relative of modern flying squirrels. Far less was known about its skull, due to a lack of suitable fossils. Now that a well-preserved cranium has been found, it turns out to be remarkably similar to that of living flying squirrels, with a slightly smaller, but similarly-shaped brain, at least some of which must surely be down to its gliding lifestyle.

Speaking of rodents, it has long been thought that the largest ever to have lived was Josephoartigasia, a mighty relative of the living pacarana, itself a moderately large South American rodent. A new study, based on the comparative size of the skull suggests, perhaps disappointingly, that it may not have been quite so large as previously thought, perhaps weighing “just” 480 kg (1,000 lbs) about eight times larger than the largest living rodent, the capybara.

Just how

the Miocene monkey Homunculus from Argentina is related to other South American monkeys has been a bit of a puzzle. A new study showed that the interior of its nose had an entirely unique structure, suggesting that it has been difficult to place because it isn’t closely related to any living species, but instead represents a very early branch that died out not long after, rather than being a primitive titi monkey, as one of the more popular theories had proposed.

Another new paper described three fossils of Jefferson’s ground sloth (Megalonyx jeffersonii) found together at a site in Iowa dating back 106,000 years. The evidence suggests that the three animals died at the same time. One is one of the largest such sloths yet discovered at an estimated 1286 kg (1.4 tons) but what’s more interesting is that another appeared to be a juvenile and the third a sub-adult. This implies that the animal must have lived in social groups, with some young hanging around with their parents even after new young had been born; based on their size, the authors estimate that the sloths would have live for 19 years and reached sexual maturity at around the age of six or seven.

Thalassocnus was a very different sort of sloth, generally interpreted as being semi-aquatic, browsing on seaweed in shallow coastal waters. A new discovery from Argentina is a long way from previously known fossils, and at a location that, even then, would have been nowhere near the coast. Clearly, the lifestyle of at least one species of the genus was more complex than we had previously thought.

Xiphiacetus was undoubtedly aquatic because it is a type of early dolphin; the name means “swordfish-whale” in reference to its unusually long and narrow snout. A new fossil is the first to be discovered outside the North Atlantic – it lived along what was then the south coast of Austria. Analysis of the skull suggests that it had efficient biosonar (something not previously known of its long-extinct family) but that it could not move its head rapidly, and so was more likely a leisurely forager along the bottom of shallow seas rather than a snap-feeder.

An analysis of an as-yet-unnamed Late Miocene rorqual suggests that, in life, it may have been over 14 metres (47 feet) long, making it the largest rorqual of its time, and suggesting that such whales became larger earlier than we had thought… although the fossil is only an ear-bone, so who knows?

Early Mammals

While they have, of course, been evolving for just as long as any other mammal, the egg-laying monotremes are often thought of as the most “primitive” living mammals. Their fossil record is relatively poor, despite the fact that the most recent molecular analyses suggest that their history must stretch back at least 200 million years to a time when even dinosaurs were still relatively new (and none of the famous ones yet existed). A new review attempted to organise what we know, proposing a new classification scheme based around three extinct families in addition to the two alive today – that is, the platypus and the echidnas.

Two points in the new scheme are particularly notable. One is the erection of a new family for the oldest known monotreme, which also happens to be the smallest. Teinolophos, which dates from 125 million-year-old deposits in Victoria was about the size of a shrew and may have already had the electrosensory organs in its snout that platypuses use to detect invertebrate prey in water. The other is a new genus name for the “giant echidna”. Now known as Murrayglossus, this lived in Western Australia during the Ice Ages (not that Australia was itself icy at the

time) and was over half-again the length of the largest living echidna.

During the reign of the dinosaurs, mammals were generally small, although describing them all as shrew-sized would not be accurate. Pantolambda was one of the first mammals to reach roughly the size of a sheep, and lived just a few million years after the asteroid impact. Despite its great age, it proved possible this year to perform chemical analyses on its teeth that gave insights into its development and early growth. Technically, it wasn’t a placental mammal, in the sense that it is not descended from the earliest common ancestor of living placentals, but the estimate is that its pregnancy lasted for a full seven months, and it

would have suckled from its mother for only one or two months after birth. This means that the young were born relatively large and well-developed, quite unlike those of marsupials, and that what we’d now think of as the placental mode of reproduction evolved very early on.

[Art by Mauricio Anton, from a paper released under a Creative Commons license.]

No comments:

Post a Comment